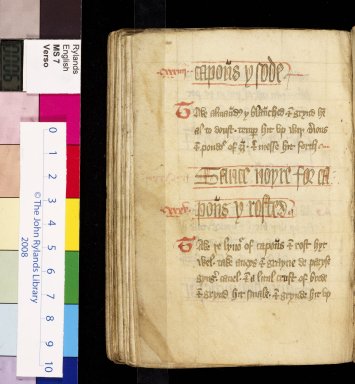

In the English Medieval court of King Richard II, around 1390, the chefs were getting excited, for King Richard himself had asked them to produce a cook book. The “Chief Master Cook” began compiling recipes cooked in the Royal court of the time and wrote them down on vellum (calfskin) scrolls. By 1420 there were more than 100 pages of recipes of this Anglo-Norman cuisine of the time, which later became known as “The Forme of Cury” or the proper way of cooking.

It was Samuel Pegge in 1785 that took these vellum scrolls and printed and edited what he called “The Forme of Cury – The Role of Ancient Cookery”. The recipes were written in the Old English of the medieval time and while some of the writings may be difficult for us to interpret into modern day English there are others which can be clearly understood. For example ‘Frytour of erbes’ is obviously Herb Fritters, the book suggests an accompaniment – ‘and ete hem with clere honey’.

The book describes, as was the custom of the time, how grand feasts began with giant elaborate sculptures made of sugar, pastes, jelly and wax. These were called sotiltees (subtleties) and would have been of ships, towers, castles or depicting current events. They were also known as ‘warners’ to forewarn the guests that dinner was about to be served.

There are recipes for ingredients that we are familiar with today such as venison but also for the more unfamiliar beaver, pike, porpoise and lampreys. Medieval macaroni makes an appearance called ‘Makerouns’ a dish of noodles and cheese. While ‘Loseyns’ a baked pasta and cheese concoction sounds very similar to lasagna. Then there is ‘Blank Maunger’ which must be an early form of blancmange which is a sweet dish made from meat, sugar, milk and almonds.

Here is a recipe from ‘The Forme of Cury’ for a sort of sausage meat ball pie called ‘Raphioles’.

Take swyne lyuours and seeŝ hem wel, take brede & grate it; and take yolkes of ayren, & make hit sowple, and do ŝerto a lytull of lard caruoun lyche a dee, chese gratyd, & white grece, poudour douce & of gynger, & wynde it to balles as grete as apples. Take ŝe calle of ŝe swyne & cast euere by hymself ŝerin. Make a crust in a trape, & lay ŝe balles ŝerin, & bake it; and whan ŝey buth ynowy, put ŝerin a layour of ayren with powdour fort and safroun and serue it forth.

Or

Take swine livers and boil them well, take bread and grate it; and take yolks of eggs, & make it supple, and do there-to a little lard carved like a dice, cheese grated, & white grease, powder douce & of ginger, & wind it to balls as great as apples. Take the caul of the swine & cast ever by himself there-in. Make a crust in a pan, & lay the balls there-in, & bake it; and when they be enough, put there-in a layer of eggs with powder fort and saffron and serve it forth. (Powdour fort was a mixture of ground spices, usually containing pepper and/or cloves and other spices).

"Reproduced by courtesy of the University Librarian and Director, The John Rylands University Library, The University of Manchester".