The news of another restaurant going under sends anxious ripples to the rest of us left standing in our clogs. For every restaurant that closes, at least a dozen or so cooks are now jobless, not to mention an even larger number of front-of-the-house staff.

We’re all feeling the pressure. And if you’re not, you should because the pool of unemployed, yet very qualified and talented, workers is growing—fast. This is a frightening reality, especially for the rest of us who still have jobs.

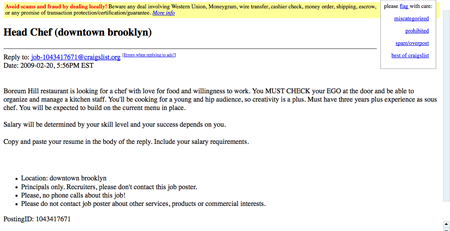

A friend of mine recently saw a job posting on Craigslist for a kitchen position at a restaurant he had recently

staged at—and one of

Frank Bruni’s Top Ten Restaurants of 2008. Having believed that their kitchen staff was solid, he casually brought it up with his friend—the sous chef—one day.

The sous chef, unaware of any available positions, turned around and asked the chef about the ad. It turned out that the position up for grabs wasn’t officially available, as in the-soon-to-be-fired-cook was clueless about his impending doom. “I’m not supposed to say anything,” he tells me.

Unfortunately, it could happen to the best of us, even the head honcho. The chef who opened a restaurant in Manhattan was recently fired for “inappropriate conduct.” When owners got word that the chef was involved with a front-of-the-house manager, he expressed his disapproval of the matter, deeming the offending chef untrustworthy. Truth be told, it all came down to money: the owners replaced him with another chef for half the chef’s salary, under the table, at that.

It’s a rough market right now and because of it, a cook’s dispensability has become a stark reality during these times of economic hardship. What was once the attraction of a cook’s life—the transient quality, the flexibility, and the availability of work—no longer holds true. But restaurants are hiring, says a sous-chef at a Manhattan 3-star restaurant—they’re just able to weed out the bad cooks because they are more of them to choose from. “We used to just hire anybody because we needed more bodies in the kitchen. But now that we can’t afford as many cooks we have to replace the bad cooks with better ones,” she added. It’s more economical. We get it.

So what does it take to keep your job? Well, for a sous-chef at a neighborhood spot in the West Village in Manhattan—one who was lucky enough to have been chosen over another recently fired equal—it was her heart and dedication to the job, she was told. “I couldn’t believe it. I was sure I was going to get canned,” she said to me. “He has twelve years of cooking under him. And he’s a way better cook than I am!” A passionate and green cook seems more economical in the books than a qualified soundly paid chef—it’s hard to know the real reason.

Ruthless management practices are certainly common in the restaurant industry—we all know that. But these days, tighter budgets seem to prompt harsh decisions regarding the payroll. And it’s not just cooks and servers scoping the restaurant listings—non-restaurant urbanites who were recently laid off are spilling over onto our turf. “I get Wall Street friends who were servers back in college calling me and asking if I have anything available,” says Kevin Garry, general manager of L’Artusi in Manhattan.

You don’t need me to tell you that the competition is heating up. But it’s turning out to be a positive correlation: the more restaurants that close, the more valuable your job is.

Work hard. Work smart. And good luck to everyone.